You gotta love the Yellow Rectangle. Richard Lovett writes for National Geographic that the The Holocene Working Group (HWG), as ably led by Dallas Abbott of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, has new work out. [Giant Meteorites Slammed Earth Around AD 500: Double impact may hvae caused tsunami, global cooling].

It seems the HWG has confirmed the presence of craters of some nature in Australia’s Gulf of Carpentania — just as predicted by the HWG using their ‘chevron’ dunes as pointers. (CT will get a hold of the source publication asap.)

For years Abbott, of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, has argued that V-shaped sand dunes along the gulf coast are evidence of atsunami triggered by an impact.

“These dunes are like arrows that point toward their source,” Abbott said. In this case, the dunes converge on a single point in the gulf—the same spot where Abbott found the two sea-surface depressions.

The new work is the latest among several clues linking a major impact event to an episode of global cooling that affected crop harvests from A.D. 536 to 545, Abbott contends.

According to the theory, material thrown high into the atmosphere by the Carpentaria strike probably triggered the cooling, which has been pinpointed in tree-ring data from Asia and Europe.

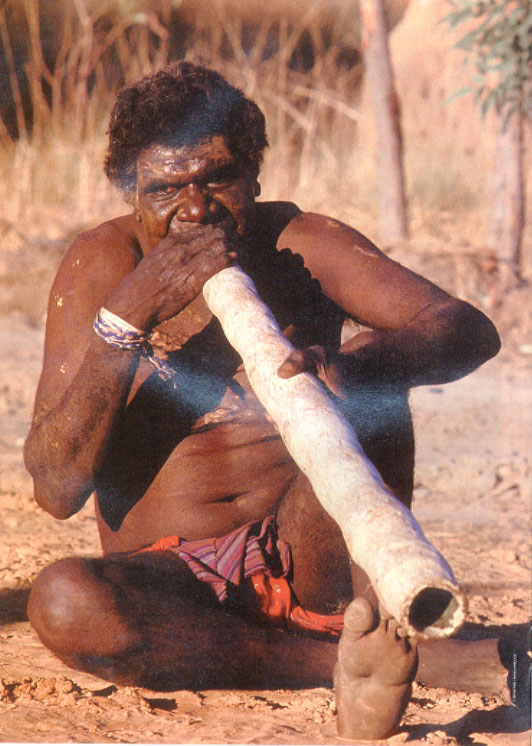

What’s more, around the same time the Roman Empire was falling apart in Europe, Aborigines in Australia may have witnessed and recorded the double impact, she said.

But wait……it gets better. Dallas and the gang gain support from an independent researcher of — get this — aboriginal oral histories. I bet whatever happened would make you drop your Didgeridoo and run for the hills.

The always skeptical and increasingly quoted Mark Boslough of Sandia Lab then weighed in. Mark seems to have made a single criticism:

We have a pretty good idea about how many there are and what the frequency of impact should be, and the abundances based on [the working group’s claimedcrater count] are orders of magnitude greater than what astronomers observe, Boslough said. It’s pretty hard to imagine where these things could be coming from so that astronomers wouldn’t see them. Mark Boslough – Sandia National Laboratories