The Washington Post

Smithsonian Magazine

University of Cincinnati press release

Comet Research Group member Ken Tankersley and his University of Cincinnati team published an astonishing paper this week in Nature’s Science Reports providing hard data suggesting that the Native American “Hopewell Culture” witnessed and suffered terribly from a cosmic onslaught just 1700 years ago.

[pdfjs-viewer url=”http://vgm.a23.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/hopewell-paper-1.pdf” attachment_id=”16323″ viewer_width=100% viewer_height=800px fullscreen=true download=true print=true]

The Cosmic Tusk is closely associated with the Younger Dryas Impact event 12,800 years ago. But regular readers know that this blog’s mandate is larger and includes all “comets and asteroids during human history,” as it says up top. Many impacts and airbursts have occurred throughout the human experience, before and since the YDI, right up until modern times.

But impact deniers persist in their belief that NASA’s (flawed) impact frequency estimate are the final word, and that no one need go poking around for archaeological evidence of impacts during the human experience. Thank goodness for intrepid researchers like Tankersley and his team.

Look and ye shall find!

Did an exploding comet help end an ancient Native American culture?

The Washington Post

Feb. 4th, 2022

The earth was scorched and covered with ash. Buildings vanished, leaving nothing but charred marks in the soil where posts had been. Temperatures on the ground may have reached 1,400 degrees Fahrenheit.

Native Americans told of the sun falling from the sky and described a great horned serpent that dropped rocks from the heavens.

And after the event about 1,700 years ago, on a spot in what is now southwestern Ohio, scientists believe the Indians created a huge earthwork image of what they had seen: a streaking comet.

This week, experts at the University of Cincinnati said the explosion in the atmosphere of a piece of that comet — an “air burst” — could have led to the unexplained decline of the Hopewell culture, which flourished in the eastern United States from about 100 B.C. to about 400 A.D.

Their research was published Tuesday in the journal Scientific Reports.

The team, headed by anthropologist Kenneth Tankersley, described evidence of what must have been devastation among the extensive native communities of the Ohio River Valley, chiefly in southern Ohio.

But Tankersley said in an interview that the researchers could not determine how many people may have been killed.

“Without a time machine, we can’t say for certain,” he said Tuesday. “But everywhere we excavated … we found burned earth, fire hardened.”

He added, “We also found burned villages.”

At one site, he and his colleagues discovered “ash-covered surfaces with post-molds filled with wood charcoal,” they wrote.

At another site, the earth looked as if it had been exposed to heat from a blast furnace, and limestone “had been thermally reduced to lime,” a process requiring a temperature of about 1,400 degrees Fahrenheit, they reported.

“The Ottawa talk about it as a day when the sun fell from the sky,” Tankersley said, referring to a tribe from the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada. “It would have been that bright. If the air burst occurred during the daytime, it would have been as bright as the sun.”

If a similar event took place over New York or Washington, D.C., today, he said, “it would be mistaken as a thermonuclear device having gone off.”

The “air burst” happened roughly between 252 and 383 A.D., more than 1,000 years before major European contact with the Western Hemisphere.

“It’s not the idea that the air burst killed everybody,” Tankersley said. “But rather that it was a catastrophic event” that caused the socioeconomic breakdown of the culture.

Tankersley said the blast was probably similar to the explosion over the Tunguska River in Siberia in 1908, which flattened forests for hundreds of miles.

The Iroquois speak of a Sky Panther, Dajoji, which has the power to tear down forests. “That’s what happened in Tunguska,” he said. “It’s the exact same thing.”

The Hopewell are the genetic ancestors of the Iroquois, the Miami, the Lenape, the Shawnee and the Ojibway, said Tankersley, who is a member of the Piqua tribe of Alabama.

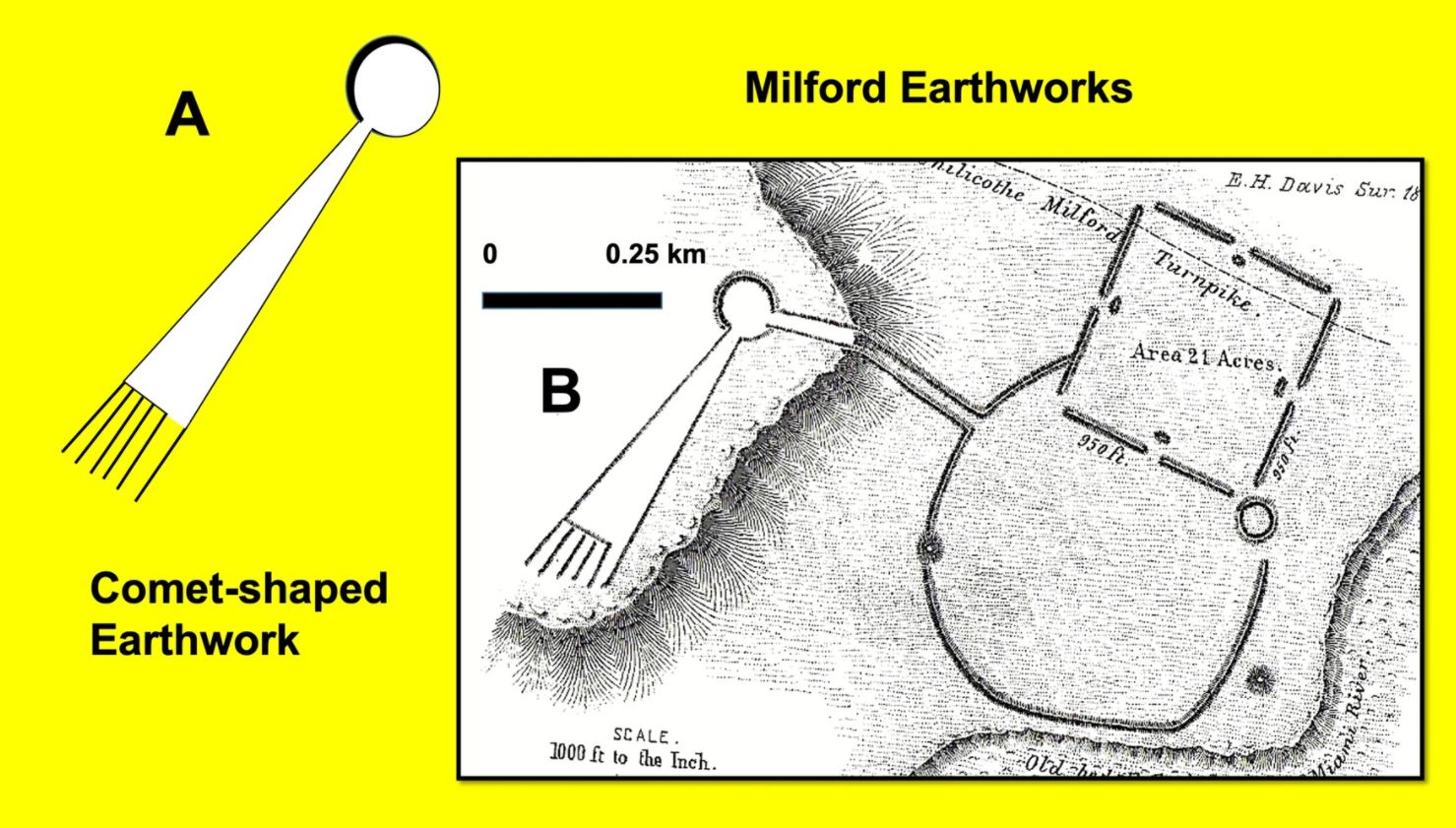

A drawing of the comet-shaped Milford earthwork based on E.G. Squier and E.H. Davis’s 1848 “Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley.”

They built “monumental landscape architecture,” the authors of the study wrote, including the largest geometric earthen enclosures in the world, water management systems and massive burial mounds.

They also had a social network that reached from the Atlantic Ocean to the Rocky Mountains, and from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, the authors wrote.

The name Hopewell comes from Mordecai C. Hopewell, who in the 1890s owned land where a massive earthwork complex that included 29 burial mounds had been found outside Chillicothe, Ohio, according to the National Park Service.

“The true tribal names of these people were lost over the millennia,” the Park Service says on a webpage about the Hopewell.

Tankersley said the Hopewell archaeological sites contained diverse material that probably came from the jumbled makeup of a comet, which is like a big, dirty snowball that picks up debris on its travels.

One day during the third or fourth century, based on radiocarbon dating, a chunk of a passing comet was broken off by Earth’s gravitational pull, he said.

It plunged into the atmosphere, where its frozen gases exploded and showered debris on the planet’s surface.

The suspected comet could have been any one of 69 believed to have passed close to Earth during that period, including Halley’s comet, which visited in April 295 and in February 374, Tankersley said.

He said excavation and research showed that the mysterious comet-like earthwork in Milford, Ohio, was built after the explosion because suspected comet remnants were found below the level of the earthwork.

The site is now beneath a local cemetery and has mostly disappeared, Tankersley said. But the earthwork had a flaring tail a half-mile long and a head more than a quarter-mile around, according to a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers map drawn in 1823.

It was also illustrated in a book published in 1848 by the Smithsonian Institution called “Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley.”

“This is a great example of Native Americans documenting their own history,” Tankersley said — the Hopewell record of the disaster that may have ended its culture.

George where is the original comments thread ? Thanks , Stuart Hamish

And do you have archived copies of the comments sections ?

I noticed Ken Tankerseley is the co author of a paper examining the evidence for the Kansas Brenham Impact Event dated to 1329 – 1470 CE George …Are Ken and his colleagues aware the earliest 14th Century carbon dating ages correspond not only to chronicled comet sightings , quakes, poisonous mists and destructive meteor strikes in Europe, Asia – and probably the southern hemisphere – corroborated by ice core and peat mire geochemical data , but also the unresolved depopulation and final abandonment of the Mississipian Cahokia civilization in neighboring Missouri and Illinois after 1350 CE – at precisely the time plague and climatic chaos were wreaking havoc in the Old World ?

Of interest to Chandra Wickramisinghe and his fellow astrobiologists are the first documented emergences of the Black Death pathogen in Mongolia and China in the 1320’s [ See ‘ The Arrival and Spread of the Black Plague in Europe , M Snell , July 30 2019 ] that just so happen to coincide – starting circa 1320 – with dramatically reduced growth /temperature in northern and southern hemisphere deondrochronologies , biomass burning signals in the south Pacific , abrupt temperature downturns in the North Atlantic and Icelandic Shelf SST anomaly series and anecdotal records of a mass fatality meteor storm in China and a possible late June Beta Taurid swarm blotting the sun red for hours and flecking the lunar surface with black smudges [ reminiscent of the 1994 SL9 impacts on Jupiter ] observed in France in 1321 as reported in John Kelly’s ‘ The Great Mortality ‘ :

[ i] 1321 – 1323 – ” It rained iron to the East of of Lake Erh – hai . Houses and hill tops were damaged with holes .Most of the people and animals struck by them were killed . It was known as the “iron rain ” [ Meteorite falls in China and some related human casualty events ‘ , K Yau et al , Meteoritics 29 , 864-871 , Aug. 1994 ]

[ii] 1321 – ” at the end of June during a solar eclipse [ I suspect the solar eclipse anchored the description of the Beta Taurid meteor stream influx in the minds of eyewitnesses ] in Anjou and Touraine [ for ] a period of four hours on the twenty sixth , the afternoon sun appeared swollen and horribly engorged as if bursting with blood ; then during the night ,hideous black spots dimpled the moon as if the craters …”

Whether bacteria or viruses drifted down from cometary debris ” downwind of the Himalayas’ or terrestrial pathogens mutated into lethality as a consequence of the mix of chemicals in the atmosphere is a matter for future investigation . If it can be confirmed the Black Plague contagion originated in China or Mongolia in the 1320’s Chandra’s theory takes on a whole new dimension of credibility . In my humble opinion Chandra and the late Fred Hoyle have prevailed in this controversial debate as the convergence of conditions is much the same template as the 530’s and 540’s leading into the Justinian Plague